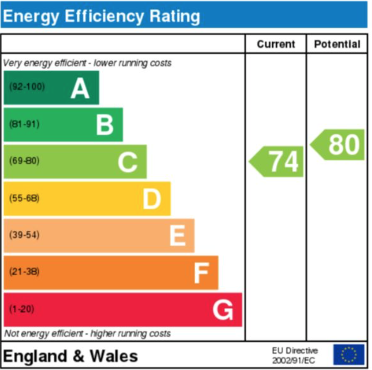

An Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) in the UK rates a property’s energy efficiency from A (most efficient) to G (least efficient), showing potential fuel costs and carbon emissions, and is required when selling, renting, or building a home. It provides a visual rating, similar to a fridge’s sticker, plus recommendations for improvements, like better insulation or efficient lighting, with potential cost savings, and is valid for 10 years.

So the EPC shows Energy Efficiency Rating with a letter grade from A (best) to G (worst) based on the building’s fabric and services. And on the energy use front, the estimated energy consumption and costs.

The improvement recommendations have specific, cost-effective ways to boost efficiency, with potential ratings and savings listed. So you may need one when selling a property; when renting out a property (as a landlord) and when a new building is constructed. This whilst an EPC is valid for 10 years.

So its purpose it quite clear, to help prospective buyers or tenants understand running costs and environmental impact and its a legal requirement – Failing to get one when required can lead to fines.

The question then to be asked is whether EPC has any impact house prices, indicating the housing market responds to the energy efficiency and climate change matters?

There is growing evidence that the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of a property in the UK does tend to be reflected in its price. That said: how much it matters depends a lot on context (location, property type, buyer priorities, etc.). Here’s a breakdown of what research and market data show, and where the limits lie.

Why and when do EPC tend to affect property price needs to be asked. Here a large-scale academic study — tracking over 333,000 dwellings sold more than once — found a positive relationship between energy efficiency (as measured by EPC rating) and sale price per square metre. The effect was especially noticeable for flats and terraced houses.

For Wales , a recent study of ~192,000 transactions showed that homes rated in bands A/B had a ~12.8% premium, and C-rated homes ~ 3.5% premium, compared with D-rated homes. Meanwhile, homes in poorer bands (E, F) carried statistically significant discounts (–3.6% and –6.5% respectively).

More recent analyses confirm the trend: a report by Oxford Economics (2024) finds that buyers are willing to pay on average ~ 3.4% more for a high efficiency home (A/B) compared with D-rating, and expect discounts for poor-performing houses.

Real-world market analyses show similar size effects: according to one survey, improving a property’s EPC from a low band to a higher one could add ~£13,000 in value on average, all else being equal.

In short: energy efficiency (and thus lower running costs) appears to factor into what people are willing to pay. This makes sense: lower bills and more modern, efficient homes tend to be more attractive — especially in the context of high energy prices or environmentally conscious buyers.

But it’s not the only or always the main factor, as the same research shows that other variables often dominate price — location, size, property type, local amenities, market conditions. EPC is often a secondary factor. The premium or discount attributable to EPC also tends to shrink when you move within the middle bands (e.g. C vs D) as opposed to the extremes (A/B vs E/F).

Some research and industry commentary emphasise uncertainty or variability: improvements needed to bump an EPC rating (insulation, heating upgrade, etc.) can be costly — so not every buyer will pay a premium high enough to reflect those costs.

For certain markets (older properties, rentals, or where EPC isn’t heavily considered), the “green premium” may be weaker or negligible.

So if you’re buying or selling: EPC is a real factor, especially in the current market where energy costs and environmental awareness influence buyer behaviour. Improving EPC rating (or buying a property with good EPC) can reasonably expect a price benefit, though exact numbers vary.

If you own a property rated low (e.g. E, F, G), you may see a discount relative to similar homes with better ratings. Conversely, investing in insulation, heating improvements, or other eco-upgrades may yield a respectable return — but only if potential buyers value those improvements.

If you’re a landlord or investor: the importance of EPC is rising, especially as regulation and tenant demand push for energy-efficient homes. Good EPC could make a property more attractive to renters, and may also support a higher resale value when you come to sell.

The wider context tells us the size of the premium depends heavily on region, type of dwelling, and what raters have assumed about the property’s structure. For instance, flats and terraces tend to show stronger EPC-price correlations than detached houses. So caveats need to be made.

The research for Wales suggests that discounts for low-EPC homes are statistically significant, but not always massive — meaning other features (floor plan, location, condition) still matter a lot.

So not all homes with high EPC will sell at premium — and EPC isn’t always the deciding factor. Buyers may prioritise other factors (neighbourhood, size, layout, condition) especially if energy cost savings don’t offset the price difference.

All properties in the UK have EPC. To what extent do they affect the house prices, if at all?