The movement of the US and Chinese embassies in London represents two of the most significant diplomatic shifts in the city’s modern history. While both moves were driven by a need for modernisation and consolidated operations, they have faced vastly different political and public receptions.

On January 20, 2026, the UK government officially approved the Chinese “super-embassy” plans, marking a pivotal moment in this long-running saga.

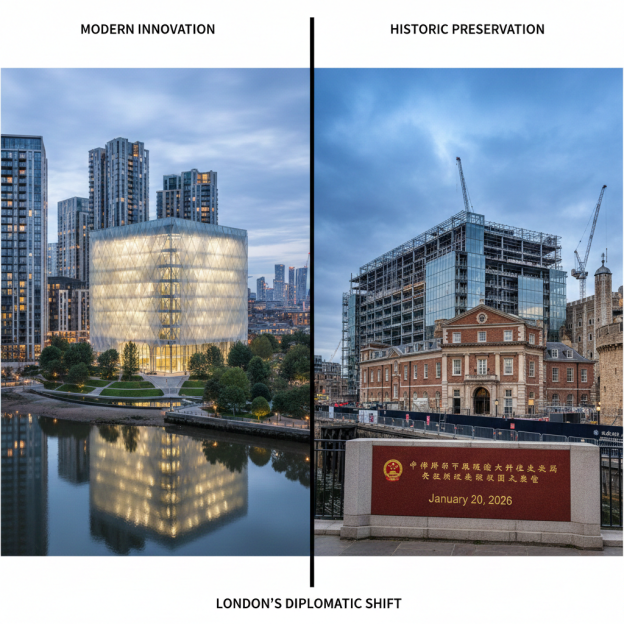

Comparison: US vs. Chinese Embassy Moves

Key Contrasts

1. Public and Political Reception

-

The US Move: While Donald Trump famously criticised the move as a “bad deal” (complaining about the “off-location”), the primary local tension was about the urban impact of security bollards and the loss of the historic Mayfair landmark. It was largely seen as a logistical and security-driven upgrade.

-

The Chinese Move: This has been a geopolitical flashpoint. The UK government repeatedly delayed approval due to security concerns from MPs and intelligence agencies. Critics argue the site’s proximity to City of London data cables poses an espionage risk, while human rights groups fear the embassy will be used to monitor and harass Chinese dissidents living in the UK.

2. Architectural Identity

-

US (Modernist Innovation): Designed by KieranTimberlake, the building is a 12-story crystalline cube. It uses advanced sustainable materials like ETFE “sails” and avoids traditional fences, instead using a pond (moat) and raised earthworks for defence.

-

China (Historic Preservation): China purchased the Royal Mint Court, a Grade II listed site near the Tower of London. Their plan involves preserving historic facades while building a massive complex behind them. It is set to be the largest diplomatic mission in Europe, covering roughly 20,000 square meters.

3. Urban Regeneration vs. Local Friction

-

Nine Elms (US): The US embassy served as the “anchor tenant” for the massive regeneration of the Battersea/Nine Elms area. Its arrival spurred the construction of thousands of luxury apartments (Embassy Gardens) and the Northern Line extension.

-

Tower Hill (China): The move has faced intense local opposition. Residents of Royal Mint Court have raised concerns about being “evicted” or living under constant surveillance. Unlike the US move, which helped create a new neighborhood, the Chinese move is viewed by many locals as an “encroachment” on an existing community.

Current Status

As of today, the Chinese embassy move has finally cleared the hurdle of government approval. However, local residents and rights groups have already signalling their intent to launch a judicial review, meaning legal challenges could still delay construction for months or years.

Because this site is uniquely sensitive—sitting directly atop fiber-optic cables that carry data for the City of London—the approval came with a “range of protective security measures” developed by MI5 and GCHQ.

While the government has kept the most sensitive technical details classified, the following specific conditions and mitigations have been made public or discussed in Parliament:

1. The “Consolidation” Mandate

One of the primary security conditions is the mandatory consolidation of China’s diplomatic presence. Currently, China operates out of seven different buildings across London.

-

The Condition: China must move all its various functions into this one site.

-

The Security Logic: British intelligence argued that monitoring one large, centralized hub is significantly more efficient than tracking activity across seven disparate locations. It effectively “shrinks the map” for UK counter-espionage teams.

2. Protection of Critical Infrastructure (Data Cables)

The most controversial aspect of the site is its proximity to a major BT telephone exchange and the fiber-optic “veins” of the UK’s financial sector.

-

The Mitigations: Though not fully disclosed, the government has implemented “red lines” regarding the basement and underground works. Reports indicate that specific “no-dig” zones or reinforced “buffer layers” have been mandated to prevent physical tapping or electronic interference with the cables running beneath the Royal Mint Court.

-

The “Hidden Chamber”: Intelligence services reportedly scrutinized plans for a 200-room basement and a “hidden chamber” close to these cables to ensure they could not be used for signal interception.

3. Public Access and Protests

A major point of friction was how the embassy would handle public space, given that the Chinese government wanted to restrict movement around the perimeter for “security.”

-

The Resolution: The UK government mandated that the site must allow for public access and peaceful protest. This was a “red line” to ensure that the embassy did not become an unreachable fortress that suppressed the rights of Hong Kong, Uyghur, or Tibetan protesters who frequently gather at Chinese diplomatic sites.

4. Vetting of the Supply Chain

As part of the planning process, the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) was involved in reviewing the technical specifications.

-

The Condition: There are strict limits on the types of integrated technology allowed in the construction. The UK government has been wary of “embedded” surveillance tech within the building’s own infrastructure that could be used to monitor the surrounding Tower Hill and City of London areas.

5. “Quid Pro Quo” Security for the UK

A diplomatic “security” condition also existed in reverse. China had effectively blocked the UK’s own plans to renovate its embassy in Beijing as a retaliatory measure for the London delays.

-

The Agreement: A condition of this approval is a reciprocal agreement that the UK’s diplomatic mission in Beijing is granted the same permissions to modernize its own secure communications and facilities.

Summary of the “Red Lines”

| Risk Category | Mitigation/Condition |

| Espionage | Consolidating 7 sites into 1 for easier surveillance by MI5. |

| Data Tapping | Strict “red lines” and structural limits on underground/basement construction. |

| Transnational Repression | Guaranteed public access for protesters and dissidents. |

| Sovereignty | Reciprocal approval for the UK’s embassy in Beijing. |

Despite these measures, the approval remains highly controversial, with the opposition and local residents’ associations already preparing a judicial review to challenge the decision in court later this year.